Powerful Questions: Work Smarter with the Answers You Get through the Questions You Ask

As leaders of volunteers, communication and discovery are integral to being effective in our job. It anchors the work we do, whether it be within our organization as we have conversations with volunteers or colleagues, or externally as we focus on recruitment and engagement. As we navigate our way through our day-to-day activities with questions – asking them and answering them – it’s important to consider if we’re focusing on the right ones. Are we looking for more than YES and NO as answers? Are we using questions to drive our work?

This Training Designs explores how powerful questions can be applied to our work as volunteer engagement professionals, allowing us to work smarter and with more impact. This article explores what powerful questions are, how to create them, and what they evoke. It also explores three specific areas of the work that is integral to volunteer engagement: interviews; orientation and training; and support and supervision. Through these deep dives, we will uncover how to adapt and integrate powerful questions into our daily work.

Powerful Questions: What they look like and how to create them

In their publication, “The Art of Powerful Questions: Catalyzing Insight, Innovation, and Action,” authors Eric E. Vogt, Juanita Brown, and David Isaacs categorize powerful questions as those that:

- Generate curiosity in the listener;

- Stimulate reflective conversation;

- Are thought-provoking;

- Surface underlying assumptions;

- Invite creativity and new possibility;

- Generate energy and forward movement;

- Channel attention and focuses inquiry;

- Stay with participants;

- Touch a deep meaning; and

- Evoke more questions.[1]

Powerful questions can be applied to three specific areas of the work integral to volunteer engagement and each area’s focus: interviews (channels attention and focuses inquiry); orientation and training (generates energy and forward movement and stays with participants); and support and supervision (stimulates reflective conversation).[2]

Anatomy of a Powerful Question

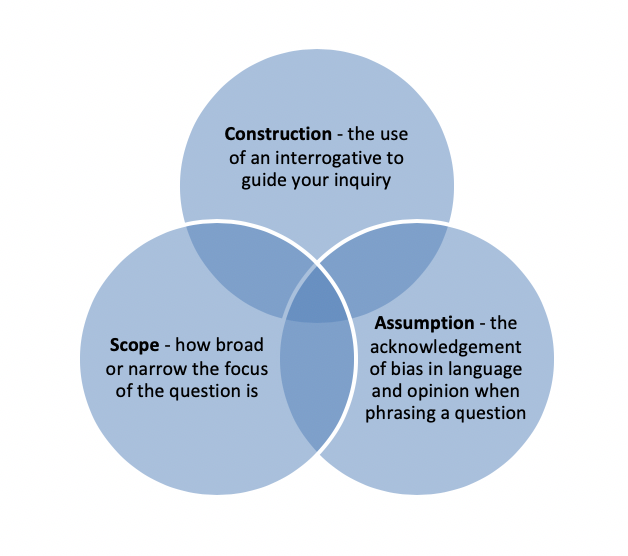

Before exploring the connections mentioned above, it is important to understand the anatomy of a powerful question. There are three dimensions to powerful questions: construction, scope, and assumptions, each of which builds on the other to create a powerful inquiry and get you a better answer. Consider this illustration: [3]

Construction

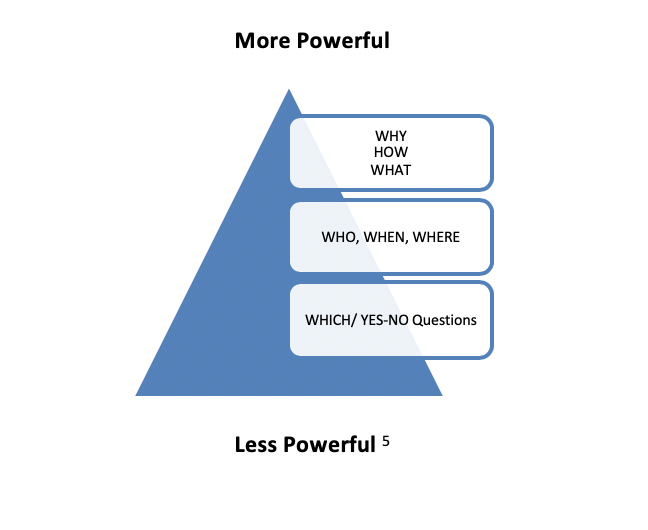

Powerful questions have a dramatic impact on how open an answer will be given, and the use of an interrogative, such as “how” or “what” in the construction of these questions helps to allow for more robust responses and therefore results.[4] A visual representation of the language used to construct a powerful question (from high to low, based on which words generate a more reflective answer) is below: [5]

When wanting a rich and detailed answer, begin questions with the words “why,” “how,” and “what” versus “who,” “when,” “where” or any question that can be answered with a simple "yes" or "no."

In addition to the anatomy of a powerful question, it is helpful to identify some key attributes – which can vary depending on the purpose of your conversation. David Gurteen includes numerous attributes in his e-book, “Conversational Leadership.” A few of those attributes include:

- The question is short and precise;

- The question is singular in nature (*a powerful question is usually a single question – not multiple questions wrapped up in a single sentence. Though often two related questions wrapped into one works well); [6]

- The question is open ended;

- The question is provocative;

- The question does not contain assumptions;

- The question is not leading;

- The question focuses on actions or behaviors; and

- It engages people and provokes them to think deeply. [7]

It is important to be able to identify these attributes to recognize how powerful questions are constructed to be able to craft them yourself and apply them to your work.

Now that we have established what powerful questions are and how they are built, let’s talk about how they relate to our work as leaders of volunteers. Let's look specifically at the following areas of common work: interviews, orientation and training, and support and supervision.

Depending on the organization you work for, your volunteer application form may gather a variety of information, collected from various standard questions. There might be a few “open” questions, but more than likely they wouldn’t qualify as powerful questions. The purpose of the interview is to determine fit between the role and the applicant’s skills, experience, and interests. While the application form can identify some potential “right fits,” it is through the design and use of powerful questions during the interview that we are able to determine which candidate is best suited for the role. Consider the types of questions you currently ask in your volunteer interviews. While one interview objective is often to hear more about specific experiences in an area or with a similar role, there are underlying characteristics that also help to identify the presence of transferrable attributes that will potentially help a volunteer be successful in a given role. Let’s look at two versions of a question for a common role and examine the differences between the resulting potential answers.

Volunteer Driver

Common Question: Client privacy and confidentiality are key standards to maintain with this role, do you have any concerns with being able to do so?

Powerful Question: Can you share with me an experience that will demonstrate how you handled having to execute your judgment in regards to whether or not to maintain confidential or personal information?

Follow Up: What did you learn from this experience?

Looking closely at these two questions. With the information learnt so far, it is easy to identify the differences between them. While an answer of “NO” to the common question will establish that the volunteer candidate has no concerns, it fails to establish for us whether or not the person has any experience with this type of situation. Even if we were to follow up with, “please give an example of when you had to maintain privacy and confidentiality” the response would yield a summary of an event or scenario, but not tactics used, or lessons learnt. In addition, the general question was leading in nature. By identifying the importance of client privacy and confidentiality, we are leading the candidate to answer in a certain way, regardless of true questions or concerns that might exist around this requirement. Looking at the example of a powerful question with the same objective, we can see that we are opening the door to an answer that is not only unbiased with our preference, but also allows the candidate to choose a scenario to explain, where they either did or did not maintain confidentiality and privacy. What this answer will present us as the interviewer is an understanding of not only experience with and around information that is confidential and private in nature, but also the candidates’ use of judgment and rationale, which are fundamental to the role of volunteer driver. The “HOW” in the powerful question allows the candidate to explain a process or train of thought, as opposed to the factual summary of the follow up to the general question. With the powerful question follow up, we allow for further self assessment of the candidate to be reflective of their experiences and learnings.

Fundraising Committee Chair

Common Question: Can you provide an example of when you had to share responsibilities as part of a group or committee, the role you played in the division of work and if the outcomes were successful?

Powerful Question: In leading a team, why is delegation important and what steps do you take to determine how much control you should keep or give to your peers or teammates?

In comparison, even with the common question for the fundraising committee chair, this example is “more powerful” than the general question for the volunteer driver, but is still isn’t a powerful question in the sense we are looking for. It is easy to think that it might be, with the identification of the word “when” in reference to the powerful pyramid above, but with the answer, will we get anything more than a summary experience? Perhaps, depending on the candidate. However, as skilled volunteer engagement professionals it is our responsibility to ask the best questions possible, for both the role and the candidate’s benefit. What makes the powerful question above such a good example is that it not only includes two questions wrapped into one skill or topic, but it does so in a way that asks the candidate to consider two of the most powerful interrogatives – why and what. Both offer a chance for the candidate to be reflective of their leadership style – which helps to speak to their overall suitability for the role. Let’s assume one of the responsibilities outlined in the position of Fundraising Committee Chair is delegation. By highlighting its importance in the powerful question sample, we are not leading the response, as it has already been identified as a part of the role. By sharing why they deem delegation important, you will be able to measure if they will truly fit into the dynamic of your desired committee. Next, by having them explain the steps they usually take to determine what elements or deliverables they maintain control over and conversely what they will delegate, we get insight into what kind of leadership style the candidate has and whether it aligns with organizational values and culture and whether it would be a fit with the team they’d be joining.

Consider This:

As Volunteer Engagement Professionals, we have a number of objectives when interviewing. Integrating powerful questions into the interview process generates thoughtful and considerate responses, yielding the opportunity to understand what differentiates a good candidate from a great candidate. It also gives us the opportunity to uncover an applicant’s unrealized skills and aptitudes that could be better suited for an entirely different opportunity that benefits our organization.

Orientation and Training

Orientation and training is designed to “provide clear information about the mission, values, and policies of the organization and the specific tasks, procedures, and scope of the position.”[8] Whether or not we are the ones delivering the orientation and training, the ultimate goal is to empower a volunteer to have a better understanding of the organization and their role, and to equip them to be successful. If done well with the help of powerful questions, we can generate energy and excitement that moves a volunteer forward and helps training stick.

Let’s look at two examples of how we can use powerful questions as part of the orientation process to better equip volunteers to become knowledgeable organizational ambassadors.

Beyond presenting information about the mission, vision and values of your organization, consider asking each participant to come ready to share their answer to a powerful question, such as “can you share an example of how you have benefited from the guidance or mentorship of someone else?” This question is powerful in a few ways; it allows a new volunteer to reflect on their own experiences, and sharing this experience in a group setting helps to establish connections to the others in the room and builds a sense of community. This is just one example of using a powerful question to build more active participation during an orientation and making this part of onboarding as impactful as possible.

To ensure we have as many skilled ambassadors as part of the organization as possible, we recognize that orientation is a significant opportunity to help make this happen. Instead of asking generic yes or no comprehension questions at the end of orientation, we instead ask a response to the following powerful question: “What would your elevator pitch about the organization be if tomorrow morning you are riding to the 47th floor with a millionaire looking to make a donation?” and collect the answers. You could keep these answers and revisit the responses with the volunteers as part of the check-in process, offering them the opportunity to respond to the question again. The original question is still a powerful question, but asking “What experiences have you had to make you answer this differently?” is even more powerful; it allows a volunteer to demonstrate their deeper understanding of the organization and realize how much they have learned and, hopefully, been inspired and touched by the mission. If a volunteer struggles with this question, it can flag a need to adjust either our approach to the initial orientation, or the training and follow-up that comes after.

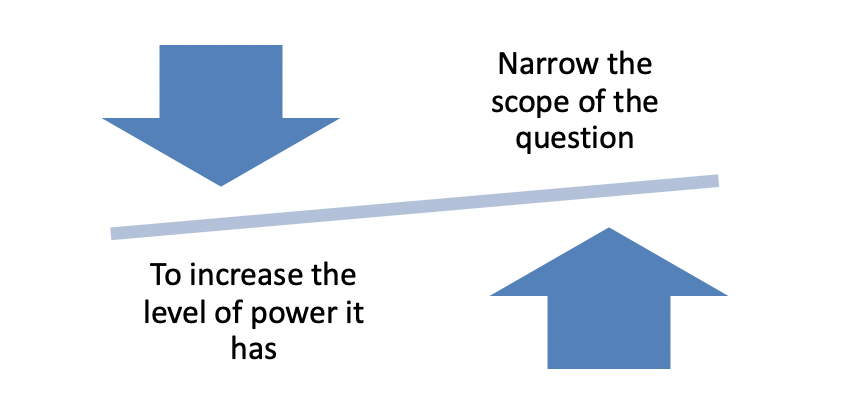

Scope

Using the same scenario, we can look to how powerful questions can be integrated into training. But first let’s review the second dimension of Vogt, Brown, and Isaac’s anatomy of a powerful question – namely, scope. Ultimately, Vogt, Brown, and Isaac say that while the words we choose can influence the effectiveness of a question, so too can the scope. By tailoring and clarifying the scope of a question to be as focused as possible, you will impact how powerful a response you receive: [9]

Using our scenario organization, pretend we have just trained someone to be an “interview coach,” a role focused on helping new immigrants prepare for job interviews. This role focuses on helping to prepare clients to understand social cues and language, as well as how best to structure responses and help the client highlight their top three skills. However, an interview coach also sees that the clients need to learn to adjust to social and cultural realities of their new community (this is actually a separate program that the organization delivers, one that the interview coach learned about during general orientation). Below are three questions you could use to empower a volunteer to self-reflect as an interview coach after supporting a client, questions that demonstrate the importance of scope:

|

QUESTION |

SCOPE |

IS IT POWERFUL? |

OUTCOME |

|

1) What does the client need and what do I need to do to help? |

- Broad - General - Non-specific to the role |

The use of “what” as reflection adds power as opposed to “does the client need help?” but the scope weakens the impact. |

Could potentially leave the volunteer to shift their focus beyond the role they are trained for. |

|

2) What aspect of interviewing does the client need the most focus on in their interview preparation sessions? |

- More specific to the role in question - Too narrow in assessing any other needs of the client |

Yes – it is powerful, as the volunteer is analyzing the most important need of the client as it pertains to their role. |

Does not address any additional needs the client might have, which could result in the volunteer acting as a roadblock to other potential resources. |

|

3) What aspect of interviewing does the client need the most focus on in their interview preparations sessions, and what are any other resources/programs I can direct them to? |

Most effective use of scope, as this question offers multi-layers: - Specific to the role in question - Engages the volunteer’s depth of knowledge of the organization’s programs |

This example is the most powerful because it not only achieves the same as question No. 2, but it also adds a second similar question that will require deeper thought. |

Multiple layers of reflection for the volunteer, with potential benefit for the client. |

Consider This:

Orientations and trainings can be more effective with the inclusion of powerful questions. Adding powerful questions allows us to review the effectiveness of the sessions and ensure they become experiences that increase the momentum of the organization, our work, and the impact of volunteers.

Support and Supervision

It doesn’t take years and years in the field of volunteer engagement to know that support and supervision – which provides volunteers the “ability to give and receive feedback” – should be integrated into all the work we do.[10] Two practical examples of how and when volunteer engagement professionals can include powerful questions in support and supervision? When dealing with conflict and when offering role evaluation.

Assumptions: Questions during conflict

When using powerful questions as a tool to help resolve conflict, it helps to look at the third and final dimension of Vogt, Brown, and Isaac’s anatomy triad – assumptions. They argue that based on the nature of our language, almost all questions that we pose have an inherit assumption built in, whether implicit or explicit.[11] The powerful question example that they give is one that aligns nicely as an example of how we might approach a conflict between two volunteers. Rather than asking “What went wrong and who is responsible?”, an effective way to eliminate assumption from the conversation would be to rephrase the question: “What can we learn from what happened, and what possibilities do we see now?” This allows for reflection and hopefully collaborative solutions, as opposed to assuming error and trying to assign blame.[12] Sometimes there are clear indications on what actions need to be taken to rectify a situation; more often than not, however, scenarios like that are the exception. The majority of conflicts we deal with are rooted in misunderstandings, unclear expectations, or a lack of communication. Powerful questions help resolve conflict by gaining deeper insights into situations and feelings. This type of reflection is crucial in moving towards resolution and also accountability. Some questions that you might want to consider the next time you approach a conflict resolution based discussion include:

- What is your role, and what part of this situation do you own?

- What are the values that each of you bring to the team/situation/project?

- What are you going to do, or what do you need to help move things forward?

Consider This:

Professor Alison Wood Brooks identifies two findings that are relevant to the example above and how to manage assumptions and conflict when it comes to asking questions. The first is that tone and group dynamics play a big part in the answers we get, regardless of how deep the question might be. Secondly, she finds that there are four main types of questions:

- Introductory questions;

- Mirror questions;

- Full switch questions (ones that entirely change the topic); and

- Follow-up questions, which result in the solicitation of more information

Follow-up questions signal that you (the listener) cares, wants to know more, and that you are being respectful to the other person.[13]

Questions for feedback and evaluation

The second way powerful questions can be used during support and supervision is when providing feedback or evaluation. Let’s explore how by adding powerful questions to this stage, we can expand the capacity and outcome of these conversations or reflections. Rather than offering only a satisfaction or exit survey, consider a combination of that with a verbal exit interview, giving volunteers the opportunity to share insights into program realities and role satisfaction. Powerful questions can help to ensure that we are working smarter. Some great examples to consider include:

- What expectations did you have coming into this role? Were they met, exceeded or not reached?

- What tells you that you were effective in your role? (if they were)

- What if anything needs to be added or removed from the responsibilities of this role, and if added, what support needs to be in place?

Powerful questions present us with the opportunity to continue to provide support and feedback at any stage of a volunteer’s involvement with the organization. Over time, a volunteer’s interests, capacity and skills can shift or evolve. Open dialogue rooted in powerful questions that evoke self awareness can help to identify if a role change may be appropriate before it becomes a necessity, (perhaps solving future problems or conflict before they arise). As leaders of volunteers, we need to be aware that our role is to be constantly assessing the “right fit.” And we need to realize that it is not a moment in time determination, but an ongoing focus for both the volunteer and the organization (us).

Conclusion

Through an examination of what a powerful question is, and how to build one, we have been able to reflect on the impact they can have on our work in volunteer engagement. As leaders of volunteers, we are in a unique position to be constantly asking questions and collecting information – sorting it, making sense of it, and making it work smarter for us. Powerful questions drive inquiry and possibility in our work. If we are taking the time to converse and ask questions with the hope of having the most impact, we need to make sure our questions are strategic and give us the answers we truly need.

Integrating the use of powerful questions as a regular and intentional part of our interviewing, training and orientation, and support and supervision can allow us to maximize our efforts to have more information at our finger tips, encouraging and resulting in more innovation, creativity, and proactive change.

What opportunities for powerful questions will you consider adding to your daily work in volunteer engagement, and why do you think doing so is important?

[1] Eric E. Vogt, Juanita Brown and David Isaacs, The Art of Powerful Questions: Catalyzing Insight, Innovation and Action (California: Whole Systems Associates, 2003), 4.

[2] Vogt, Brown and Isaacs, The Art of Powerful Questions, 4.

[3] Vogt, Brown and Isaacs, The Art of Powerful Questions, 4-5.

[4] Vogt, Brown and Isaacs, The Art of Powerful Questions, 4.

[5] Vogt, Brown and Isaacs, The Art of Powerful Questions, 4.

[6] Gurteen, David, “How to Design Powerful Questions” in Conversational Leadership, https://conversational-leadership.net/powerful-questions.

[7] Gurteen, David “How to Design Powerful Questions” in Conversational Leadership, https://conversational-leadership.net/powerful-questions.

[8] Volunteer Canada, “The Screening Handbook: Tools and Resources for the Voluntary Sector: Building a Safe and Resilient Canada,” Public Safety Canada, 2012, https://volunteer.ca/vdemo/researchandresources_docs/2012%20Edition%20o….

[9] Vogt, Brown and Isaacs, The Art of Powerful Questions, 5.

[10] Volunteer Canada, “The Screening Handbook: Tools and Resources for the Voluntary Sector: Building a Safe and Resilient Canada,” Public Safety Canada, 2012, https://volunteer.ca/vdemo/researchandresources_docs/2012%20Edition%20o….

[11] Vogt, Brown and Isaacs, The Art of Powerful Questions, 5-6.

[12] Vogt, Brown and Isaacs, The Art of Powerful Questions, 5-6.

[13] Alison Wood Brooks and Leslie K. John, “The Surprising Power of Questions,” Harvard Business Review, May-June 2018, https://hbr.org/2018/05/the-surprising-power-of-questions.